Tuesday, May 27, 2014

A College Education is Still a Good Investment

The end of the month is near, and soon I will be making my now-ritual three payments for the debt my wife and I accumulated for our undergraduate and graduate educations. Though these payments are a burden and have been for the many, many years we have been paying them (and will be for many more years in the future), I have never once regretted the decision to go into debt to finance my education. I am firm in the belief that it was an exceptional investment both economically and personally.

Which is why I worry a bit about all of the focus on the rising debt that college students are accumulating. The basic takeaway there is the effects of states dramatically reducing their support for public higher education. This is something that, as a society, we should be concerned about, but not something that suggests college is no longer worth it. A college education it is still a good investment even at the much higher tuition rates state universities are charging.

So I was pleased that the exceptional new New York Times blog The Upshot, which is led by the exceptional David Leonhardt (three cheers for getting him back on the economics beat) posted this graph today along with a great write up. Yes, college is not only still with it, but ever more so as time goes by.

Friday, May 23, 2014

Friday Frivolity

Its Friday afternoon so I'll write about my third favorite subject (behind economics and beer): soccer. There seems to be a lot of consternation among the US Soccer pundit class about the snub of Landon Donovan.

I am a little perplexed. As a Timbers fan who got to see Landon live and in action two weeks ago, I was stuck by the fact that he had very little impact on the game. I was also struck by how clearly heavy and slow he was. He did not look at all like the lithe, fast, skillful Donovan of the past.

Which is all to say that I am not at all surprised by his being dropped. With the cup thee weeks away there is no hope of his regaining the required fitness he needs in time. And for those who think he could be a useful sub, it seems to me that what you want from a sub is either someone who can come on and bring some energy and danger when you need a goal, or who can help shut things down. Neither of these describes Donovan in his current state.

I am a little perplexed. As a Timbers fan who got to see Landon live and in action two weeks ago, I was stuck by the fact that he had very little impact on the game. I was also struck by how clearly heavy and slow he was. He did not look at all like the lithe, fast, skillful Donovan of the past.

Which is all to say that I am not at all surprised by his being dropped. With the cup thee weeks away there is no hope of his regaining the required fitness he needs in time. And for those who think he could be a useful sub, it seems to me that what you want from a sub is either someone who can come on and bring some energy and danger when you need a goal, or who can help shut things down. Neither of these describes Donovan in his current state.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Tuesday, May 20, 2014

Fred Thompson: Capitalism Is Biased In Favor Of Capitalists II

This is the second in a two-part review by Fred Thompson of Thomas Piketty's book: Capital in the 21st Century. The first part was posted yesterday.

Given Piketty’s narration of the

German case, it’s mildly surprising that he doesn’t give greater attention to

corporate governance, which is very much a product of deliberate policy –

perhaps because they were products of deliberate policy. As he notes, his theory fails

in the German case when he uses stock market valuations instead of book value.

Why? Because, under the German “stakeholder model” of corporate governance,

shareholder rights to cash flows are relatively weak. German managers/directors

have broader obligations than their American counterparts and greater

discretion to pursue growth and stability at the expense of profitability.

Consequently, they throw off far less of the economic value their businesses

generate to shareholders; instead, they retain more of it, presumably in the

best interests of the remaining stakeholders.

Anglo-American shareholder activism, together with

various tax policies, seems to have had two effects, a large and sustained

increase in the value of publicly traded shares (the main driver of β in the economy) and a decline in the economic weight

of publicly traded enterprises, whether measured in terms of output or

employment shares, relative to privately-held businesses. Bankers and fund

managers aside, more than anyone else, the owners of these enterprises have

benefited from the economic growth of the past 30 years or so. Moreover, since

the 1986 tax act they have been able to avoid double taxation by extracting

profits from their businesses in the form of wages (and precluded from

expensing personal consumption to their businesses). Consequently, business

owners’ reported (and very likely their real) incomes have soared since the

enactment of the 1986 tax act.

Unfortunately, we cannot say for certain exactly how

much. The Haig-Simons income (Y) definition –

consumption plus the change in wealth (∂K) – is the standard one in the

literature – the Platonic ideal if you will of income (i.e., GNY = C+S, where S

= ∂K). Wealth (K) is the present value of the future income stream associated

with the bundle of property rights comprising one's endowment, which is a

stock. The change in wealth (∂K) over a finite period is a flow. We don’t

measure any of these things directly, but instead infer their values from data acquired

for other purposes: collecting taxes primarily and

measuring aggregate consumption. As a result, exactly how

much real income inequality has increased in the U.S. is open to question, and the

timing and causes of this phenomenon are even more so.

Nevertheless, most analysts agree that income inequality

has increased greatly over the past 30 years. Fortunately, we can fix this via

public policy. Taxing capital income when it's realized, rather

than when it is reported, would be a good start. Indexing financial assets to

inflation would clearly be better than the current favorable treatment of

capital gains. Taxing inheritances (depending upon the property tax regime,

perhaps, excluding real property) is also an attractive prospect. But an array

of policies aimed

at broadening gain sharing ought to be considered, including a rethink of

corporate governance policies and practices.

The evidence on wealth inequality is less clear-cut. The fact is that by most measures, including financial, wealth (K)

has increased relative to income (Y) but is no more unequally distributed in

the US now than in the fifties and sixties. Atkinson and

Morelli (2014), for example, conclude that wealth was actually more unequally

distributed in the U.S during the great compression than now. One might think

that increased income inequality would necessarily lead to increased wealth

inequality, since wealth is simply the cumulative excess of income over

consumption, but that isn’t the case where the distribution of wealth is more

unequal than the distribution of income, which is apparently still the case in

America.

Even if one uses Piketty’s rather circular wealth

estimates, increasing wealth inequality is a phenomenon that applies only to

the top 0.1 percent of households (the top 130,000) and a fortiori to the top 0.01 percent (13,000). It would be interesting

to see

who these folks are. It’s my hunch that a majority of

them are business owners not the scions of inherited wealth or their corporate

minions. Regardless, it seems unlikely that increased wealth inequality is the

main driver of income inequality in the U.S.

Moreover, Piketty’s analysis is concerned

entirely with private wealth. It excludes all publicly owned assets, the assets

owned by nonprofits, and the present value of future social security and the

proceeds from defined pension plans. SSI, for example, is indexed to the CPI,

which means, other things equal, it has grown faster than the rest of the

country's wealth portfolio. But other things are not equal; the population is

rapidly aging further increasing its PV. Apportioning that wealth is difficult,

but it probably makes sense to do so.

Finally, there is one further question that

you are probably asking yourself if you have gotten this far is “won’t r go

down too?” This is obviously a soft point of Piketty’s model and the source of

the circularity in his wealth estimates. He summons a lot of historical

evidence to show that r has generally been stable during the last two centuries

despite massive changes in the K/Y ratio. But that doesn’t mean that he is

right and he’s clearly challenging one of the fundamentals of economic theory:

decreasing returns to a relatively abundant factor of production.

Clearly, I am not entirely persuaded by

Piketty’s every claim. Nevertheless, I was blown away by Piketty’s book. If you

want to read something challenging and extremely informative, read this book.

Monday, May 19, 2014

Fred Thompson: Capitalism Is Biased In Favor Of Capitalists I

This is the first in a two-part review by Fred Thompson of Thomas Piketty's book: Capital in the 21st Century. The second part will be posted tomorrow.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century is a marvel without

precedent: serious economic scholarship – a dynamic model of economic growth

and the distribution of wealth – that is also a runaway best seller.

Piketty’s basic conclusion is that capitalism

is biased in favor of capitalists – no big surprise there. His model consists

of an identity, two mechanisms, and a mathematical inequality (the same as the

modern Darwinian synthesis, probably our best known dynamic model). The

identity links the stock of capital (K) or wealth to the flow of income (Y).

The stock of capital includes all forms of explicit or implicit return-bearing

assets: housing, land, machinery, financial capital in the form of cash, bonds

and shares, intellectual property, etc. The identity is expressed by the ratio

between K and Y, or β. The share of capital incomes in total national income

(α) is equal to the rate of return, in real terms, on capital (r) multiplied by

β.

The mathematical inequality links the rate of

return (r) and the rate of growth of the economy (g) to income inequality – if

r>g, which Piketty argues is the natural state of things, then α increases

by definition, driving up the share of capital (wealth) in national income. As

Nobel Laureate Robert M. Solow observes: “This is

Piketty’s main point, and his new and powerful contribution to an old topic: as

long as the rate of return exceeds the rate of growth, the income and wealth of

the rich will grow faster than the typical income from work.” Consequently,

Piketty concludes that in the long run the economic inequality that matters

won't be the gap between people who earn high salaries and those who earn low

ones, it will be the gap between people who inherit large sums of money and

those who don't.

Over the long span of history surveyed by

Piketty, the only substantial period in which g>r was between 1910 and 1970

(in the U.S., 1933-1973, the period Goldin and Katz call the “Great

Compression”). Piketty ascribes this to the destruction and high taxation

caused by the two world wars and the Great Depression. He is dismissive of

deliberate policies: “Neither the economic liberalization that began around

1980 nor the state intervention that began in 1945 deserves much praise or

blame. The best one can say is that they did no harm.” Consequently, he is

indifferent to most of the literature on the political economy of this era,

with its attention to regimes of (capital) accumulation and modes of regulation

(the institutions, policies, and practices governing the operation of

accumulation regimes). Moreover, the French case matches up with his

formulation quite nicely. Capital-income ratios held steady at about seven from

1700 to 1910, fell sharply from 1910 to 1950, reaching a low of a bit less than

3, then began to climb, by 2010 to about 6. Furthermore, Piketty provides

pretty compelling evidence that in France increased wealth led increased income

inequality.

Certainly, recovery from war and depression, as

well as deep structural factors related to demographics and technology, help

explain the burst of rapid economic growth following World War II.

Nevertheless, it is a mistake to account for the mid-20th Century period of shared growth exclusively

in terms of large, impersonal economic forces. Politics and institutions also

mattered. Indeed, I would argue that the political and economic arrangements of

the postwar era were qualitatively different from those that preceded and

followed it and that this distinctive set of policies profoundly influenced the

pace and content of economic development and the subsequent distribution of

income, consumption, and wealth.

This view of the postwar era assigns a key role

to organized labor, which was then at the apex of its power, not only in the

social-democratic states of Northern Europe, but throughout the industrialized

West. Organized labor was politically decisive in its support the welfare

state, Keynesian full-employment policies, high inheritance and income tax

rates, heavy reliance on payroll taxes, and capital and foreign exchange

controls. The upshot of these policies included a vast expansion of mass

production and consumption, widely-shared wage gains and “profitless growth” – what

Michel Aglietta calls the Fordist regime of capitalist accumulation in A Theory of Capitalist

Regulation: The US Experience (2000).

Mass production thrives on economies of

scale. Consequently, as Robin Marris explained in The Economic Theory of Managerial Capitalism (1964), under mass

production, most output is supplied by a smallish number of large enterprises,

usually publicly held corporations, where managerial control is separate from

ownership. Marris argued that in the immediate postwar era managers exercised considerable

discretion, which they used primarily to grow their enterprises rather than to

maximize shareholder wealth, since they generally got higher salaries and

greater status from running bigger businesses – hence, profitless growth. He

also argued that this was socially desirable: growth-seeking firms make

countries grow faster (g up, r down).

Obviously the postwar boom couldn’t go on

indefinitely. Declining population growth, satisfaction of long stifled wants,

and catch-up on the part of Europe’s capitalist economies and Japan to the

technological frontier would have probably curbed economic growth in any case.

The problem of integrating baby boomers into a workforce, which was already

beginning to shed manufacturing jobs, further stressed the Fordist system of

accumulation, leading to wholesale changes in its characteristic modes of

regulation: fiscal policy was subordinated to monetary policy or, perhaps more

accurately full employment subordinated to price stability, inheritance and

income tax rates slashed, capital controls eliminated, and exchange rates

floated.

Arguably, the demise of the Fordist

accumulation regime followed, in part, from its success. Increasing mechanization

and computerized production hollowed out the blue-collar workforce in the

industrialized West and led, thereby, to the marasmus of labor movements. Mass

production shifted to the developing world where wages are low and

environmental quality standards lax. Both developments reduced political

support for policies aimed at broad-based gain sharing. Moreover, activist

investors, especially in the English speaking world, increasingly found ways to

use the market for corporate control to discipline hired managers and stock

options and bonuses to align managerial interests more closely with theirs –

away from growth and toward maximization of shareholder wealth. As Solow put

it, in his respectful review of Piketty’s book: “It is pretty clear that the

class of super-managers belongs socially and politically with the rentiers, not

with the larger body of salaried and independent professionals and middle

managers.”[1]

[1]

One ought not push this conclusion very far, however. At any point in time

there are only 500 Fortune 500 CEOs

in the U.S., 0.5 percent of the 0.1 percent.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Oregon Unemployment Steady at 6.9% With Addition of 6,100 Jobs in April

Another good month for Oregon jobs in April. Oregon added 6,100 jobs in April on a seasonally adjusted basis following a robust 8,900 in March. This means the Oregon job market is growing at a 2.6% clip, substantially faster than the US average of 1.7%. The Oregon unemployment rate remains unchanged from March at 6.9%.

As you can see from the graphs above, we have still not recovered all the ground we lost in the great recession but we are close. The takeaway here is that hiring is pretty robust right now after years of no to very slow growth, this is a welcome change.

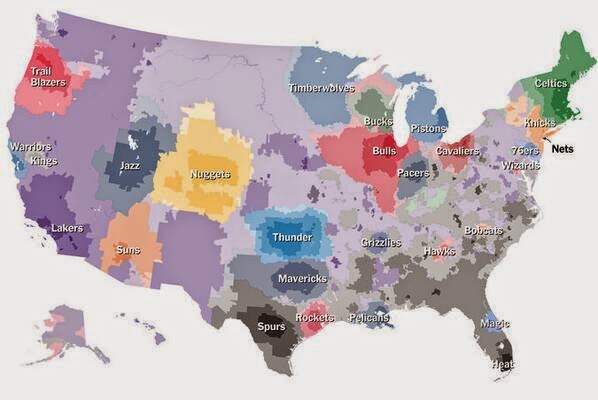

Picture of the Day: NBA

I know I have been AWOL lately, many many pressing things in real life has left me without time to blog. So today I make it all up with useless content!

From the NY Times:

The NBA fandom map. Really Washington, the Lakers?!?

From the NY Times:

The NBA fandom map. Really Washington, the Lakers?!?

Thursday, May 1, 2014

Inflation v. Productivity

This graph is from a very nice article by Annie Lowrey of The New York Times. The article is about what it means to be poor in the 21st Century USA.

But what I like about this graphic is that it shows you that inflation is an average of a basket of goods and that some goods, whose productivity has far outpaced the average across the industries in the basket, have rapidly declining prices while others, who have not seem much productivity gains at all see very steep relative price increases.

Take computers and college tuition. The latter is often used as an example of Baumol's Cost Disease, and you can see the point very clearly above: for industries such as education, where the process of learning is still very similar to what it was 100 and 200 years ago, the relative price has shot up. Why? Because the other industries, like computer manufacturing, have seen massive productivity increases. The price of big TVs today is shockingly low. And thus the number of fancy TVs you have to forgo to pay for college is going up all the time.

But this shows the danger of such comparisons which is essentially Baumol's point: we should not expect all industries to increase productivity similarly. It is, in fact, quite natural for some industries to see little productivity increases (like in his classic example, a symphony orchestra). They are not doing anything wrong which is why the term 'disease' was used - it is something natural.

Which does not mean, of course, that these prices don't hurt - they do. But my little Macintosh SE I bought as an undergrad cost about 1/5th of my private college tuition. Now a student at the same college can buy in infinitely more nice, colorful, powerful Mac for about 1/20th of a year's tuition. The notion that one price has gone 'up' while the other 'down' is a purely relative statement and only reflects the rate at which you can trade one for the other.

I wonder, though, if there is any correlation between the relative accessibility to consumer electronics and similar consumer good and the declining support for unions and other former champions of the 'middle class.' No idea...just a thought.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)