Friday, February 29, 2008

Change Oregon's Tax System? - Guest Blogger

For three-quarters of a century, Oregon tax reformers have been almost monomaniacally obsessed with the chimera of the sales tax. And, while it would be nice if we could reduce state income-tax rates by adopting a well-designed consumption tax, preferably a comprehensive value-added tax with an income-contingent rebate, I don’t believe that this would be a panacea. Its benefits would be fairly small and its costs not insignificant. Moreover, I think the likelihood that we would actually be offered the option of a well-designed consumption tax is practically nil.

So why don’t we try to fix some real problems that have workable, practicable solutions?

One problem is that the existing personal state income tax hits a lot of poor people pretty damn hard. Oregon has a flat tax, which levies the same rate on household incomes above a statutorily determined level that varies with the type and size of the household. I think this is a pretty good tax. It meets the twin tests of adequacy and efficiency pretty well and, because of the design of various exemptions, exclusions and credits, turns out to be remarkably progressive. But its progressivity has been eroded somewhat over time as inflation has whittled away the value of the statutory exemption.

One simple fix would be a one-time boost in the exempt amount, combined with indexing it to inflation. Another simple, worthwhile fix would be to increase the EITC refund.

Of course, there is no such thing as a free lunch, Boosting the statutory exemption 50 percent would reduce state revenues about $400 million per annum and increase revenue volatility (greater progressivity almost inevitably means greater volatility).

Which takes us to our second problem. Oregon already has one of the more volatile revenue structures of any of these United States, which causes all sorts of nastiness as we move through the business cycle. The problem, however, is not revenue volatility per se but the nastiness that results from trying to adjust spending up and down to match current revenue flows. Why not fix the real problem? Doing so would in fact require a couple of fairly modest institutional changes. The first would be to base the state revenue forecast on the state’s long-term, sustainable rate of expenditure growth, given existing tax-structures and demographics, rather than short-term revenue growth. By sustainable, I mean making the forecast subject to the "no-Ponzi" condition, the requirement of intertemporal budget balance. The second would be to give the retirement of general-fund debt first priority for the use of Kicker funds.

To make up for some of the revenue lost in making the personal income tax fairer, we should fix the corporate income tax. Actually, this is something we ought to do anyway.

Right now what we have is the worst of both worlds – the statutory rate is relatively high and the tax is easy to avoid. The first condition gives businesses a motive for avoiding Oregon’s corporate income tax and the second the opportunity to do so. The statutory rate should be lowered and the apportionment system returned to one that weights the location of assets, employees, and sales equally in assessing state income-tax obligations.

These are all things that could be done this legislative session. Why not do them?

Beeronomics: Block 15

Corvallis is not a big town. So it is quite a thrill to welcome Block 15 Brewery to the local beer scene. [Block 15 is the first true brewpub in town: Oregon Trail brews and serves out of the Old World Deli, and McMenamins on Monroe brews but most of the beer is imported from other McMenamins breweries] I had lunch there today while hosting the Economics Department's seminar speaker. My first impression was very favorable. I had a pulled pork BBQ sandwich (on the recommendation of Kyle Odegard of the Gazette-Times), the pork was very good, but a better bun could have improved it a lot, and an:

Corvallis is not a big town. So it is quite a thrill to welcome Block 15 Brewery to the local beer scene. [Block 15 is the first true brewpub in town: Oregon Trail brews and serves out of the Old World Deli, and McMenamins on Monroe brews but most of the beer is imported from other McMenamins breweries] I had lunch there today while hosting the Economics Department's seminar speaker. My first impression was very favorable. I had a pulled pork BBQ sandwich (on the recommendation of Kyle Odegard of the Gazette-Times), the pork was very good, but a better bun could have improved it a lot, and an:

Aboriginale: Free-style Ale. This is what Block 15 is all about, truly unique unclassified beers in addition to our standard taps. We used seven different malts, and three different hops when brewing this beer. Currently we are dry-hopping in a conditioning tank with two more types of hops.

It was very, very good - wonderful fruity hops aroma, rich head and a beautiful straw to amber color, hop-forward but nicely balanced. It sure had the strong aroma and the surface tang characteristic of dry hopping, but interestingly the dry hop language above was not on the menu and the server did not think it was dry-hopped. So it remains a mystery. I was served in a shaker pint, but was unable determine if it was honest.

They have done a great job with a very interesting space and even include an enticing mezzanine level. They have also been getting some good attention, see: here, here and here.

On top of a great space, great food and great beer, they are also very nice and, it turns out, helpful. You see, I dutifully bought the beer for myself on a separate check because OSU does not pay for alcohol on expensed meals, but I completely forgot my itemized receipt to prove it. This was quickly solved when the econ department's wonderful office manager called them up and they immediately faxed it over.

So my first impressions are very good.

Go there. Now.

The Final Verdict: No Sales Tax in Oregon

Well, the final poll results are in and reflect the general split all along: A small majority prefer not to introduce a sales tax. I suspect that it has mostly to do with concerns of regressivity and the distrust of politicians to do enough to counter it. I concede that it would be a tough political fight, but I am also quite concerned about being such an outlier on income taxes. Still my support for the sales tax waned the more I got into the morass of the data. I would support a tax package that introduced the sales tax and reduced the income tax but also made it progressive. I think, however, the ability to deduct the income tax on federal returns is a pretty big counterargument, so I would not mind a relatively high income tax along with a small sales tax.

Well, the final poll results are in and reflect the general split all along: A small majority prefer not to introduce a sales tax. I suspect that it has mostly to do with concerns of regressivity and the distrust of politicians to do enough to counter it. I concede that it would be a tough political fight, but I am also quite concerned about being such an outlier on income taxes. Still my support for the sales tax waned the more I got into the morass of the data. I would support a tax package that introduced the sales tax and reduced the income tax but also made it progressive. I think, however, the ability to deduct the income tax on federal returns is a pretty big counterargument, so I would not mind a relatively high income tax along with a small sales tax.But my readers have spoken and I am beholden to them. I have tried my best to educate (while still keeping my job - meaning having to do the tax research in my spare time) and after delivering what I hope is a fair reading of the evidence and arguments, my readers have filed to find convincing the arguments for the tax. Thus I consider the case closed. If readers of The Oregon Economics Blog don't think it is good for Oregon, than it is not.

Thanks to all who participated in the poll.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

On-Line Economics Experiment

By supporting the blog, you make the marginal cost/marginal benefit analysis tilt slightly more in favor of blogging in my off hours than, say, reading crime fiction to which I am addicted (though generally not American as it is usually terribly written - I am currently reading Swedish crime fiction, but my favorite is the Rebus series, partly because of my familiarity with Edinburgh in which they are set). However that is the substitution effect. The income effect may mean that since I am able to afford more crime novels, I will actually end up reading more and blogging less. So no guarantees.

Update on Portland Home Prices

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Beeronomics: Hops and Barley

Andrew Helm, a graduate student in the OSU Economics Department, grew up on a farm in North Dakota. Among the many crops his family farm produces regularly is barley. Andrew told me a very interesting story about barley prices. Apparently barley can be sold as malting barley and feed barley and usually malting barley (which is a bit more selective) fetches a much higher price than feed barley. But these days the prices are as close together as he can remember. What gives? One reason is that barley malters are constrained somewhat by the supply of hops, if there are no hops there is little demand for malted barley. Thus the price of malting barley has not risen as fast. On the other side, as corn has displaced a lot of wheat and barley, feed barley prices have risen in response (also, apparently you can write longer forward contracts on malt than you can on feed barley because they are traded in different commodity markets). Spiritwood is the place they sell theirs.

Andrew Helm, a graduate student in the OSU Economics Department, grew up on a farm in North Dakota. Among the many crops his family farm produces regularly is barley. Andrew told me a very interesting story about barley prices. Apparently barley can be sold as malting barley and feed barley and usually malting barley (which is a bit more selective) fetches a much higher price than feed barley. But these days the prices are as close together as he can remember. What gives? One reason is that barley malters are constrained somewhat by the supply of hops, if there are no hops there is little demand for malted barley. Thus the price of malting barley has not risen as fast. On the other side, as corn has displaced a lot of wheat and barley, feed barley prices have risen in response (also, apparently you can write longer forward contracts on malt than you can on feed barley because they are traded in different commodity markets). Spiritwood is the place they sell theirs.So the point is that the hops shortage might actually be helping to keep the barley price from rising as much as it otherwise would because the two are such strong complements in the production of beer.

Follow up (2/28/08), an e-mail from Andrew:

Patrick,

If you want to look at the spread between malting and feed barly, the following sites are the "local" sites in NE North Dakota and NW Minnesota.

http://www.farmerselevator.com/ --Alvarado- malting barly terminal

http://www.chsdrayton.com/ ---Drayton- feed barly terminal

Between these terminals- over 30 million bushels of wheat, barly, soybeans, and corn are transfered in a year.

I have not followed these prices recently, the malting price has increases from the last time I saw it quoted. Moreover, since the last time I looked, the spread is indeed widening for longer term contracts; this was not the case 6 months ago. However, the spread percentage between malting and feed is still much lower than now than it was 2 or more years ago. But wide enough, that from Drayton it is worth the cost to haul, if the barly meets malting quality.

H. Andrew Helm

Mortgages, the Fed and the Macroeconomy

Monday, February 25, 2008

Mea Culpa

It does get me thinking about how much I take for granted in terms of having good medical insurance. I simply cannot imagine having the stress of medical payments looming over the decision to have a wheezing 2 year old seen by a physician or the burden of expensive drugs. My total out of pocket bill for one office visit and two prescriptions: $10. How to design a good medical system that takes care of everyone is a tough question, but I am pretty sure we are far from optimal.

P.S. I hope to find the time and energy soon to write a post on local currency as featured in Sunday's O.

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

The Fourth Estate

This brings up two pertinent economic questions:

The first is the practice itself and if it indeed calls for legislative remedy. In this case we have what economists recognize as a classic incentives problem: the private incentive of a school district that faces a teacher who has been disciplined for sexual misconduct is to make the problem go away at the lowest cost to the school district. Thus cutting a deal to have a voluntary resignation is a very good strategy for the district. The cost of cutting such a deal is not born by the school district, but by society at large (assuming that even a small percentage of such teachers are recidivist). What do economists call such costs? Externalities. Externalities are a classic case of justifiable government intervention - often explained in terms of protecting the public interest in the face of private incentives which are opposed. However, there seems to be a couple of potential pitfalls to finding an appropriate policy solution. First, it is not clear to me how much this practice is based on allegations of misconduct, rather than confirmed cases through a system of due process. It seems to me that many school districts are simply trying to make a potential problem go away, so legislation prohibiting this practice would potentially force school districts to go through costly investigations and often costly litigation. Second, this is likely not a state problem but a national problem, so it is not clear that the remedy is a state-level one. If Oregon passes a law that says, for example, Oregon school districts must disclose allegations of misconduct to future employers, this will potential impose a huge cost on Oregon school districts and yet we may still have a large number of teachers who have been dismissed for misconduct coming into the state.

The other pertinent economic question that this raises is the fact that we rely so heavily on the news media to bring problems to our attention. If the news media really are the fourth estate and have a critical role to play in our democracy, is the for-profit model the way to go? What are the incentives of The Oregonian to do such investigation? Sales of papers. Is this private incentive enough to ensure that the socially optimal level of investigative journalism, a public good, is being achieved? No. We all benefit from this journalism whether we read the O or not, so a lot of us are free riding on this information that, once published, becomes a common property resource. Economists know that in these cases - private provision of public goods - the good is underprovided relative to the social optimum. This raises an interesting question - should the public finance investigative journalism?

Hmmm.....

Friday, February 15, 2008

More on Oregon Housing Market

The HPI is a weighted, repeat-sales index, meaning that it measures averageprice changes in repeat sales or refinancings on the same properties. This

information is obtained by reviewing repeat mortgage transactions on single-family properties whose mortgages have been purchased or securitized by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac since January 1975. The HPI is updated each quarter as additional mortgages are purchased or securitized by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The new mortgage acquisitions are used to identify repeat transactions for the most recent quarter and for each quarter since the first quarter of 1975.

It should be made clear that these data are from house purchases using conventional, conforming loans up to the limit of $417,000 - so they do not capture the 'expensive' house market which is a bit more volatile.

This second picture are the same data but expressed as percentage change from the previous quarter.

It does appear that Bend and Medford are more dramatic than other Oregon cities both in the heating up and the cooling off.

Housing Forclosures and Oregon

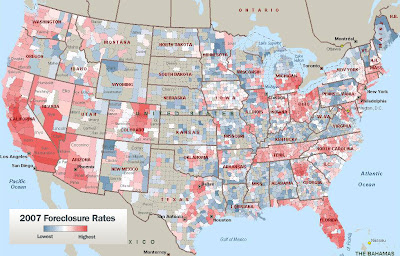

OK, here is the essentially the same foreclosure data I posted about yesterday, but for the state, not just Portland (also from RealtyTrac). Essentially the same story here, metro area is doing OK (better than many), but our state falls in the middle in this relative comparison, probably due to Portland and poor conditions in non-large metro areas relative to other states. The map below shows some extra 'heat' (in their parlance) coming from central Oregon (Bend) and Southern Oregon (likely Ashland/Medford).

Also, I am really committed to the avoidance of cross-posting, but the Paul Krugman column today in the New York Times is simply too good to pass up and is related to this post: he writes about what is happening to the credit market. This is serious, the fed it trying to inject liquidity into credit markets, but no one feels they know how to assess the liabilities of all of these financial instruments bundled with sub-primes, so it is not working - the commercial credit market has seized. His column is about how expectations guide everything, which is what makes macroeconomics so fascinating in my opinion.

Thursday, February 14, 2008

Housing Foreclosures and Portland

The picture is pretty good: yes foreclosures are up 24% over last year (percentage of households with filings), but overall Portland's percentage (0.6) is well below the national average of (1.0). I think this may turn out to be the story of the Portland housing market: Oregon's economy (especially in terms of employment) was slow to recover from the recession of 2001, this delayed the heating up of the Portland housing market and therefore it never got too over-inflated by the time of the credit market freeze due to the subprime mess. So we might just dodge a bullet on this one, though I would still expect a minor correction. At this point, the consumer credit market crunch is in full gear, and without huge supply pressure from foreclosures we may not see much of a drop in values. But the big question looming out in the distance is health of the national economy and the potential effect of a recession or extremely slow growth on the Oregon employment sector.

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

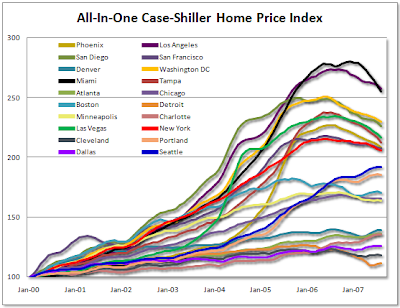

Another Look at Housing Markets and Portland

Graph from "The Mess that Greenspan Made"

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

Beeronomics: Specialization and Product Variety

Last Friday I had the distinct pleasure of having lunch with John Harris, brewmaster at Full Sail and the man responsible for, among many other amazing beers, slipknot Imperial IPA (shown here - go get some, it is fantastic). I learned many interesting things from John about the beer business including learning about an outfit called 'Microbeer Source.' A number of very small bottling breweries use Microbeer Source to bottle their beer, including Full Sail for the 'Brewmaster Reserve' line that is brewed at the Pilsner Room in Portland. Microbeer source is, you see, a mobile bottling line which brings the line to local breweries and bottles their beer for them. Upon researching this, I discovered that this is very common in the wine industry, which makes sense, the wine industry is mostly made up of many very small producers whose product is needs to be bottled in order to send to market. Bottling lines are pretty expensive, take a lot of space, and without this kind of specialization, it would be hard for

Last Friday I had the distinct pleasure of having lunch with John Harris, brewmaster at Full Sail and the man responsible for, among many other amazing beers, slipknot Imperial IPA (shown here - go get some, it is fantastic). I learned many interesting things from John about the beer business including learning about an outfit called 'Microbeer Source.' A number of very small bottling breweries use Microbeer Source to bottle their beer, including Full Sail for the 'Brewmaster Reserve' line that is brewed at the Pilsner Room in Portland. Microbeer source is, you see, a mobile bottling line which brings the line to local breweries and bottles their beer for them. Upon researching this, I discovered that this is very common in the wine industry, which makes sense, the wine industry is mostly made up of many very small producers whose product is needs to be bottled in order to send to market. Bottling lines are pretty expensive, take a lot of space, and without this kind of specialization, it would be hard for small producers to survive. Economists often talk about such industries in the context of "natural monopolies," industries where there are such high fixed costs to begin production, that the market can only support one producer (which means having large economies of scale, but in a particular way).

small producers to survive. Economists often talk about such industries in the context of "natural monopolies," industries where there are such high fixed costs to begin production, that the market can only support one producer (which means having large economies of scale, but in a particular way).In this context, if all small wineries had to have their own bottling lines, many would not be able to cover the cost of the line from the sales of their wine and would, therefore, not exist. There would not be monopoly, but the number of wineries would be drastically reduced. This is the same, albeit on a smaller scale, in the microbrewing

industry. It is unlikely that breweries like Roots, a small Portland outfit (whose "Woody IPA" is fantastic and available in bottles down here in the sticks thanks to Microbeer Source) would be able to sell in bottles without such a bottling service available to them. So, through specialization of tasks, we can not only improve efficiency (as in Adam Smith's archetypical pin maker story), but in these cases, we can improve product variety as well. For what this means for consumers of beer and wine is not just lower prices for the increased efficiency that specialization brings, but many more choices available to them when they wander into their local supermarket or beer and wine store. Ah the wonders of economic organization...

industry. It is unlikely that breweries like Roots, a small Portland outfit (whose "Woody IPA" is fantastic and available in bottles down here in the sticks thanks to Microbeer Source) would be able to sell in bottles without such a bottling service available to them. So, through specialization of tasks, we can not only improve efficiency (as in Adam Smith's archetypical pin maker story), but in these cases, we can improve product variety as well. For what this means for consumers of beer and wine is not just lower prices for the increased efficiency that specialization brings, but many more choices available to them when they wander into their local supermarket or beer and wine store. Ah the wonders of economic organization...P.S. John raised an interesting question, to which I have a number of plausible answers, but I will ask it as an open question first: why are just about all of the major bottling breweries in Oregon today the very same ones that were here 15 years ago? In other words, why have there been no new entrants into the industry in the last 15 years (with the exception of Terminal Gravity)? Ideas?

Economist's Notebook: Prediction Markets

The basic idea is this: we all have biases and make mistakes, but gather enough of us together and on average we will converge to the true mean (think of is as a 'law of large numbers of people'). But if we all make the same mistakes (too influenced by, say, an article in the NYT) or are influenced by each others behavior, we can go badly wrong. Take the last two bubbles, the dot com bubble and the housing bubble, if we are all so smart why is there a bubble?

Prediction markets may also have investors that may have ulterior motives - they support a candidate and want to improve their showing in the prediction markets so that others will think they are successful and be less reticent to support them (creating a self-fulfilling prophecy).

Still, in the end, large samples do have a tendency to minimize the individual biases if they are not all in the same direction, so these prediction markets are almost always better than polls.

Returns to Majoring in Economics

The average starting offer for seniors majoring in:

Economics: $51,631

Finance: $47,905

Marketing: $41,323

Business Administration: $43,523

Mechanical engineering: $54,587

Chemical engineering: $60,054

Management information systems: $46,568

Civil engineering: $47,145

Electrical engineering: $54,599

Computer science: $51,070

Accounting: $46,508

Logistics/Materials management: $43,294

Liberal arts (including psychology, political science history, English): $30,502

OK, so maybe engineering is more lucrative, but then there is the compensating wage differential to consider - economics is fun!

Monday, February 11, 2008

A Final Treatise on Sales Taxes

Before that, however, I have a few loose ends to fill in. The first is what George Zodrow of Rice University (who very generously sent me a copy of his book, “State Sales and Income Taxes: An Economic Analysis”) calls the "exportability" of a tax system: how well a state can export its revenue burden to residents of other states. Income taxes, as I said before have the nice feature of being deductible on federal tax returns (sales taxes have been added too in the past as a temporary measure, but you have to choose one or the other, so if we are talking about adding a sales tax along with income taxes, we loose a bit of the exportability). Deducting income taxes on federal returns shifts the burden a bit to residents of other states. But a lingering question is whether sales taxes can be good in the exportability criterion from the fact that non-residents spend money in Oregon.

I think Zodrow says it best:

The sales tax on consumer goods can be exported to the extent that such goods are purchased by out-of-state residents – primarily tourists and business visitors. This is not likely to be an important source of revenue for most states. In any case, if opportunities for tax exporting in this area are deemed to be significant, they can be exploited through the use of special taxes on hotel/motel occupancy, car rentals, and, to a much lesser extent on entertainment and admission to amusements.

To this I would add that a gas tax is also a big area in which we exploit these opportunities to export our taxes. Dean Runyan Associates does the Oregon State Travel Impacts studies for the state and I looked at their estimates. First, they report that many locales charge an occupancy tax for hotel/motel rooms – though these are local taxes, not state. They also report that food and retail spending together make up less than 40% of visitor spending. But in 2006 they estimate a total in excess of $7 billion spent in Oregon by out of state visitors – so perhaps there is room for some more specific taxes if not a sales tax in general, though we must be mindful that we are very dependant on tourism in this state and we would not want to impact it too much.

This brings me to another point, if sales taxes are enacted; will it hurt the tourism and retail sectors hard? I feel pretty strongly that they would not. I think the price elasticities would be low due to the fact that we would probably have a sales tax on the low end in the national spectrum, so we would not be abnormally expensive.

On the other hand, abnormally high tax incidences do worry me for the very same reason. So Oregon’s income tax rate, essentially the highest in the nation, worries me a lot. I have tried to

find evidence of the impacts and I have seen estimates of lower investment, job losses and increased expense for employers who have to compensate for the tax difference but overall impact on the economy is, in my mind, difficult to assess and I remain unconvinced by the evidence. But I am pretty strongly influenced by economic theory, however, which suggests that this should matter in investment and employment decisions.

Volatility is, as I said at length before, not reason enough to support a sales tax, as not much is necessarily gained by such a tax. The only real answer to volatility is either a rainy day fund, or (as was pointed out to me by Fred Thompson) allowing the government to engage in deficit spending during bad periods. The latter strategy has the appeal of not over saving which is inefficient. Equity is a concern, but income taxes have been shown to be a poor way to achieve redistributive goals (and may in fact be impossible because labor markets adjust). It is through ex-post transfers that equity gains are made in general, but we would have to be ready to devote a good portion of any sales tax to such an end if we are to avoid making our tax system more regressive.

So in the end, where do I stand? Well I would like to see a sales tax to lower the income tax incidence in Oregon. I would support it only if there were adequate exemptions and transfers that could assure we do not add regressively into the tax system. I would also like to see some type of permanent rainy day fund or the allowing of deficit spending. I think we could stand to gain much as a state in terms of investment and job creation from the lowering of the income tax and that boom and bust cycles in state spending are very inefficient. Any exportability we get from a sales tax will be countered by the loss in exportability from the lower income tax, and I don’t expect much in terms of volatility reduction except perhaps in extended downturns. I do think that, all else equal, diversification of revenue streams is a decent goal, but, more importantly, I think we should avoid being an outlier in any one tax dimension in the US.

Friday, February 8, 2008

Monday, February 4, 2008

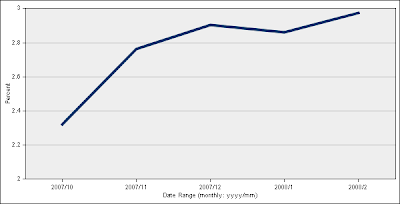

Economist's Notebook: Why Do Mortgage Rates Rise When the Fed Cuts Rates?

From the Cleveland Fed: "Because the market's expectations for inflation are priced into one of these securities, the measure that is derived from the yields is a good estimate of the market's estimate of future inflation."

We see that since the late fall inflation expectations have risen steadily. In December and January mortgage rates fell steadily, perhaps thinking that the Fed was on top of this trend, but then mortgage rates jumped back up - right around the last two rate cuts, on Jan 22 and Jan 30. I think it is pretty clear that the mortgage market suddenly started to worry quite a bit about the Fed loosing control of inflation (below is a graph of 30 year fixed interest mortgage rates).

Housing Affordability in Oregon

This first graph, above, shows all of the counties for which average home vlaues over average incomes have increased in the time period and by how much. There are also a few which decreased (below).

Friday, February 1, 2008

Beeronomics: Oh Happy Day!!

Be not the slave of your own past. Plunge into the sublime seas, dive deep and swim far, so you shall come back with self-respect, with new power, with an advanced experience that shall explain and overlook the old.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

This just about sums up how I feel about craft beer. The day I first tasted a Hair of the Dog 'Fred', everything I ever assumed I knew about beer was changed and I have never looked back (thanks Alan).

Which is why today is such a good day. Rare indeed is the day as good as the one in which you are able to get your hands on two bottles each of Full Sail's Top Sail and Deschutes' The Abyss. I now possess two of the finest examples of the brewmaster's art

. These are limited releases and don't last long. Whispers in my ear from two knowledgeable sources (thanks Jeff and John) began my quest which ended quickly at Corvallis' University Market (in case you would like a weekend as good as mine -Portland is runnig out of Abyss quickly today). They are not cheap but worth every last penny. Go. Buy. Enjoy.

. These are limited releases and don't last long. Whispers in my ear from two knowledgeable sources (thanks Jeff and John) began my quest which ended quickly at Corvallis' University Market (in case you would like a weekend as good as mine -Portland is runnig out of Abyss quickly today). They are not cheap but worth every last penny. Go. Buy. Enjoy.Which brings me to economics once again. I have been thinking a lot about preferences, experience goods, variety, branding and the Oregon craft beer industry lately. Some of this I have blogged about before. Seems to me that variety is also sometimes risky because by producing a beer at a far end of the spectrum, you may capture some first time drinkers of your brand but quickly loose them forever if they dislike what you have offered. Beer is a type of product that economists call 'experience goods,' goods whose quality you cannot determine until you consume it (as opposed to clothes, say, which you can touch, feel, try on, etc., and have a pretty good idea of the quality before you buy). Since many people more familiar with macro pilsners don't really know what to expect from an aggressively hopped Oregon IPA, it may be better to introduce them first to a milder pale ale. But you can't really control this if you are a beer company offering a lot of distinct beers - so are beer companies hurting themselves by offering too many distinct beers thus increasing the chances of a bad first encounter? What is the 'optimal' level of product variety in this case? Open questions.

Another take is that by producing beers like Top Sail and The Abyss, breweries establish their credentials with beer snobs and the beer press and add luster to their brand - somehow a Full Sail pale is that much better knowing it comes from the company that brought you Top Sail.

Once again, I understand that brewers' motivations are many, but they do have to sell to survive so economics considerations remain very important.