But the market has essentially seized. Nobody wants commercial paper (just like no banks want to lend to each other). Everyone is so freaked out that they all want to hold cash or Treasuries and want to take on absolutely no risk. It is already clear that $700 billion promised to buy toxic assets was not enough to reassure people (as I has worried it might not) to get off their duffs and start lending out their cash, so today the Fed has stepped in with a plan to buy commercial paper and directly inject liquidity into that market.

The running theme of the week so far is how bad news and jittery investors in Europe has counteracted the effect of the $700 billion bailout. We are all interconnected now. And here, as evidence, I will simply steal from Paul Krugman:

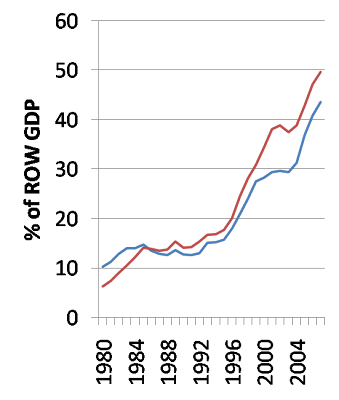

The chart above shows rest-of-world assets in the United States (red) and US assets abroad (blue) as a percentage of non-US GDP; while we talk a lot about the US as a debtor nation, what’s really striking is the surge on both sides of the balance sheet. This has made the global financial system a lot more tightly linked, so that big economies are now experiencing the kind of contagion previously associated with emerging markets caught up in the 1997-1998 crisis. We’re all Brazilians now.

What this shows is that we are trying to deal with a problem domestically that has spill-overs internationally. This begs the obvious question (which has been asked by development economists for a long time): are the integrated international financial markets so big and so integrated that there needs to be international cooperation in their oversight?

No comments:

Post a Comment